Monday, July 30, 2012

Conscious Automatism: Part One

Tonight, I speak to you as a robot -- a conglomeration of molecular machines. In fact, I have always done so, since my birth. And, matter of fact, all of you are robots, too.

A song titled conscious automata: http://vimeo.com/3051734. I thought it was pretty interesting. Sounds like the Hindu or Buddhist concept of "OM."

----

I had such a problem in class thinking about "conscious automatism" -- where our consciousness is just a result of physical, bodily events (an epiphenomenon) and every action we make is a direct result of our conditioning or some physical event that actually 'exists' in the physical world. Conscious automatism makes me really angry and for some reason it doesn't make any sense to me. My mind, my being, my body wants to resist it with such force that I almost wanted to cry in class the other day. Maybe there's some missing link here, and in it's absence, 'conscious automatism' is all we come up with.

I can choose to be sad or happy -- if I choose to be optimistic, I can see the direct effect of this on my mood (a physical quality). This leads me to ask, what is the physical nature of a choice? What exactly happens here? Does the physical world really act out a choice without any sort of intervention from an outside agent, a consciousness?

When I make a choice, several thoughts appear in my mind. I consider each thought, and have several different scenarios or images running through my head. I make comparisons, I 'weigh' the possibilities. While I am inclined to be a realist, take conscious automatism at face value, and stick solely to what is believable in the physical world, I have such a hard time subscribing to these views. Really... some molecules -- or electrical impulses-- are dancing in my brain until an epiphenomenal cloud of thoughts passes, and reveals the correct choice based on some sort of paths, logic statements, and neural gateways? I just don't get it at all. Why would such epiphenomena exist? For what reason would the epiphenomena of free will and thought exist?! Ugh, I get so angry and I don't entirely know why. (My anger is just an epiphenomenon anyways... bahahahahaha!)

Personally, I'm inclined to think, as weird as it might sound, that the body is a database and a tool for an intangible soul. The physical system stores memories and facilitates comparisons between areas of the brain, but there is something beyond the body that drives the machine. I believe it's the same for animals, too, but the amount that the soul can effect the world through them is different. I think reflexes are like autopilot on a plane. I think that our body is taught reflex mechanisms too from pain and pleasure and that memories associated with these are stored in the brain. But... still, why do the epiphenomena of pain and pleasure even exist? Why do we feel anything at all? Why doesn't our brain just learn from pain silently? Wouldn't this be the same? If we're conscious automata, if our brain had learned to not do something, we just wouldn't do it again because our bodies would refuse to act. There wouldn't have to be the epiphenomena of pain.

Maybe the epiphenomena are what help our bodies communicate with other people. Who knows. Maybe Huxley (the original author of the idea of 'conscious automatism') is right, and our thoughts are just like the whistling sound coming from a hot teapot... the thoughts themselves a superfluous result from a physical process. I just can't accept this, though, because it seems like thoughts ought to have some purpose. Ugh. I'm probably not understanding this entirely.

I once watched a documentary titled Quantum Activist (which I can't find a link to anymore) which discussed the several different ways in which quantum theory aims to justify the existence of God, the mind, etc. I would like to watch this again, and once I do, I think I will comment on it. I also plan to read a bit more on this subject, just to make sure I actually understand what I'm saying here.

Sunday, July 29, 2012

Getting in Their Heads: The Darwin Dispute

|

| Henry Fleeming Jenkin, engineer. (image: wikipedia, Henry Fleeming Jenkin). |

This past week we debated whether or not the Origin of Species was fundamentally hostile to established religion. I played the part of Henry Fleeming Jenkin (1833-1885), a professor of Engineering at the University of Edinburgh. At first I was extremely hostile to the thought of having to play the other side, because I've never doubted the validity of Darwin's theory of evolution. I also hated the fact that Fleeming Jenkin was overtly racist ... but I had to concede that this is just to be expected from Victorian society. Take a minute to look at the quote below:

"... Suppose a white man to have been wrecked on an island inhabited by negroes.... Our shipwrecked hero would probably become king; he would kill a great many blacks in the struggle for existence; he would have a great many wives and children, while many of his subjects would live and die as bachelors.... Our white's qualities would certainly tend very much to preserve him to good old age, and yet he would not suffice in any number of generations to turn his subjects' descendants white.... In the first generation there will be some dozens of intelligent young mulattoes, much superior in average intelligence to the negroes. We might expect the throne for some generations to be occupied by a more or less yellow king; but can any one believe that the whole island will gradually acquire a white, or even a yellow population...? Here is a case in which a variety was introduced, with far greater advantages than any sport every heard of, advantages tending to its preservation, and yet powerless to perpetuate the new variety." (quote: Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swamping_argument)At first, Jenkin's argument struck me as stupid. But I realize now that this was my brain putting up a wall to something that seems ludicrous when juxtaposed with 21st century understandings of genetics. After reading several analyses of Jenkin's argument, I eventually came to understand why his criticisms presented a serious problem for Darwin's Origin at the time. Fleeming Jenkin's point encapsulates the Victorian understanding of inheritance: blending inheritance. At the time the theory was published, most Victorians thought that offspring were destined to be an average between the two parents.

|

| The mechanism of blending inheritance, where the parents' characteristics are averaged within the offspring. (Image: wikipedia, blending inheritance). |

I never realized until this point how difficult it was for Darwin when his theory was first conceived. It required modern genetics for the ideas included within to be entirely acceptable. Our modern conception of particulate inheritance, based on the work of Gregor Mendel, solved the problem. Mendel worked with pea plants at the same time Darwin's theory was being contested, but the importance of his theory remained unrecognized until the 20th century. (source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregor_mendel).

|

| Particulate inheritance, as set out by Mendel. (image: wikipedia, Mendelian inheritance). |

Sunday, July 22, 2012

Have Wonder and Terror Gone Out of Style?

In class, we have discussed the 19th century discoveries of deep time and deep space, largely the result of astronomical discovery and geological discovery. In the Victorian Era, as geologists analyzed the earth, they began to realize that the visible striations within rock were layers of sediment that must have been laid out over thousands -- if not millions -- of years. Furthermore, in addition to realizing that stars and objects in the night sky were very, very far (millions of miles) away, astronomers began to believe that each of these objects (nebulae, planets, etc.) seemed to represent a different step in the cosmic process of the creation of space objects, realizing all of these objects had an inconceivably long history. Together, these observations helped provoke Victorian culture to fear and admire the natural world. Indeed, if one was inspired by these discoveries, experiencing the 'magic' of scientific discovery was not out of one's reach -- in the 19th century, the realms of astronomy and geology had been widely accessible -- all a layperson had to do was look up into the night sky or find a cliff-side to examine. These pervasive discoveries proved so important to mankind that they threatened the foundations of established religion. In light of all the new knowledge, Victorian Era Europeans struggled with how to reconcile fossil findings with discoveries in the book of Genesis. They also struggled with reconciling the possibility of alien life with God’s seemingly exclusive mention of the earth in His Bible. People began to wonder if God was watching over other worlds too.

|

| A border between two geological ages. I believe the greensand is on the left and the chalk on the right. |

|

| Geologic formations on the Jurassic Coast. All of these reveal massive geologic forces at work. |

Today, sometimes I wonder if we’ve lost a sense of awe. The night sky -- an important reason for the wonder and terror of Victorian culture -- is not widely accessible anymore. Nowadays, in most places, especially modernized ones, humans don’t see the complete night sky anymore. While looking for the social effects of this starless phenomenon, I read an interesting article this morning that talked about all the objectively detrimental issues that come with light pollution: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2627884/. Some mentioned are the effects on wildlife, but also… surprisingly… an increased risk of cancer! I couldn’t believe that at first.

One of the most disturbing statements the article mentions is the following: “Indeed, when a 1994 earthquake knocked out the power in Los Angeles, many anxious residents called local emergency centers to report seeing a strange “giant, silvery cloud” in the dark sky. What they were really seeing—for the first time—was the Milky Way, long obliterated by the urban sky glow.” What statement could describe our modern, starless condition better? Looking at my own situation, I think the first time I’ve ever seen the full night sky with the Milky Way was watching an episode of Survivor (the show was being shot in the middle of the Pacific). I faintly remember stargazing on a farm when I was younger, but I certainly don’t remember the Milky Way being there. It’s been so long since I’ve stargazed that it almost seems as if it is a dream.

Another telling figure: “According to “The First World Atlas of the Artificial Night Sky Brightness,” a report on global light pollution published in volume 328, issue 3 (2001) of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, two-thirds of the U.S. population and more than one-half of the European population have already lost the ability to see the Milky Way with the naked eye. Moreover, 63% of the world population and 99% of the population of the European Union and the United States (excluding Alaska and Hawaii) live in areas where the night sky is brighter than the threshold for light-polluted status set by the International Astronomical Union.”

I wonder what sort of effects the lack of the night sky has had on society and culture – do we focus more on ourselves now because we’re not being reminded of our minute size in comparison to the vastness of the universe? I also noticed something pretty weird when searching this morning for ‘stargazing’ on Google Scholar – all the articles that came up referred to stargazing as either a derogatory word meaning to become distracted with unrealistic dreams, or it referred to concern with the lives of celebrities. In the context of this finding, it may be that we have become more self-centered – forgetting the vast beauty of nature, we worship celebrities, and in societal consensus, choose to burn lots of fossil fuels to create awe-inspiring areas such as Las Vegas or Times Square.

Things that I am in awe of today (of course, I can’t say the night sky, because I haven’t seen it in person…

Beautiful, humongous cliffsides, trees, meadows, and beaches |

| All the pictures above are of the clifftop along Chesil Beach, Burton Bradstock, UK, on the Jurassic Coast. |

Large crowds (like the one yesterday in London)

Huge team productions like movies (aren't you in awe when all the credits roll for a movie?)

The ancient history of a fossil

The humongous human population

Grocery stores, with so many products housed inside (and this is only one of thousands or millions worldwide!)

Electricity and the internet

Flying on an airplane

Spaceships and the idea of life on other planets

Epidemic diseases (but not to the degree of the Victorians, obviously. We have far superior sanitation and health measures)

So, in light of my list, I’m left wondering -- how do my

forms of wonder and terror mold my perception of the world?

Are We Just Chemical Soup?

Today, despite all the knowledge

gained about the body and the brain – its chemicals and hormones – we still

confront age-old questions: what truly

constitutes one’s personality? Do we

have souls? If so, how are they

defined? I struggle intensely with this issue, because I

do not want to accept the modern conclusion that my emotions and perceptions arise

solely from different amounts of chemicals connecting to receptors in my brain. Such a concept undermines the notions that I

have control over my actions, that I am unique, and begins to make me feel

machine-like. I want to believe that

because I am able to think about my mind that something of me transcends my

body… but in light of modern science, this is difficult to do.

Let me set the scene with the

lyrics of a beautiful song I happened to listen to recently. It is the song O’Sister by the band City and Colour, and I believe it has great

relevance to understanding the conflicting understandings of mental illness

that still exist today. (to listen: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gi-crVagUok)

Oh sister

What's wrong with your mind?

You used to be so strong and stable

My sister

What made you fall from grace?

I'm sorry that I was not there to catch you

What have the demons done?

What have the demons done?

With the luminous light that once shined from your eyes?

What makes you feel so alone?

Is it the whispering ghosts

That you fear the most?

What's wrong with your mind?

You used to be so strong and stable

My sister

What made you fall from grace?

I'm sorry that I was not there to catch you

What have the demons done?

What have the demons done?

With the luminous light that once shined from your eyes?

What makes you feel so alone?

Is it the whispering ghosts

That you fear the most?

Chorus:

But the blackness in your heart

Won’t last forever

I know it’s tearing you apart

But it's a storm you can weather

Oh sister

Those lines etched in your hands

They're hardened and rough like road map of sorrow

My sister

There is a sadness on your face

You're like a motherless child that's longing for comfort

What’s running through your veins

That's causing you such pain?

But the blackness in your heart

Won’t last forever

I know it’s tearing you apart

But it's a storm you can weather

Oh sister

Those lines etched in your hands

They're hardened and rough like road map of sorrow

My sister

There is a sadness on your face

You're like a motherless child that's longing for comfort

What’s running through your veins

That's causing you such pain?

Does it have something to do with the pills they gave to you?

What is eating at your soul?

Was it the whispering ghost that left you out in the cold?

Chorus

Oh sister

My sister

Oh sister

My sister

I was

surprised by how much the lyrics of this song express a struggle for the singer

to understand his sister’s mental illness in corporeal terms. He wavers between ‘what’s wrong with your

mind’ to ‘what have the demons done?’ He

also seems to battle between a physical and ethereal description of the illness,

sometimes describing it as lost light in the eyes, and something ‘running

through the veins,’ but then following those terms with language such as ‘whispering

ghosts,’ ‘blackness in your heart,’ ‘storm you can weather.’ He also expresses distrust for modern psychological

drugs in the line “Does it have something to do with the pills they gave to you?” The song essentially encapsulates the

question, “Is my sister depressed or ill because of her bodily chemistry or

because of supernatural forces?”

Such existential angst has a long

history, because humans never have been able to give a wholly convincing answer

to questions of the mind. In the 19th

century, several scientists, artists, and academics began to hypothesize

connections between physical appearance and personality traits by making ‘objective’

studies of human skulls (phrenology) and faces of mental patients (the

monomaniacs of Théodore Géricault). These

conclusions were sensational and controversial; while holding a possible key to

understanding the human mind, they also threatened to undermine what many

humans hold dearest: a sense of existence that transcends the material realm.

Phrenological head diagram. As a funny note, phrenologist Orson Squire Fowler (1809-1887) believed that no apprenticeship was needed to become an architect if you had a large 'inhabitiveness' bump (love of home) and 'constructiveness' bump (ability to build). He also told Mark Twain he had a crater in his humor area, meaning that he had no sense of humor. (image: graphicsfairy.blogspot.co.uk)

Phrenology – the study of the size

of skull-bumps as indicative of personality traits – was developed in 1796 by physiologist

Franz Joseph Gall, and became very popular during the early 19th

century. The study originated from observations of aptitudes or deficiencies within

living humans: for example, because a phrenologist observed that a man with

extraordinary language skills had a prominent brow, a prominent brow became

associated with language ability. Most of

the observations were not reliant on one instance, but rather several skulls

taken from deceased animals and people that had notable characteristics. Phrenologists liked to collect skulls of extreme

cases – such as criminals and the mentally handicapped – and use those as

exemplars of certain characteristics associated with those extremes.

A series of phrenological heads from the Whipple Museum here in Cambridge. The one on the left was used as a portable head for phrenologists to carry around when studying the bumps of Victorians. The middle-left is the cast of a head of a mass murderer, and the two on the right are heads of the mentally handicapped. (image: author)

The seemingly ‘objective’ approach

of phrenology also extended into the realm of madness. 19th century European society began

to believe that people did not go mad because of their sins, but rather because

of physical characteristics that predisposed them to do so. Mental illnesses began to become classified

by their symptoms, and many ‘objective’ phrenological and observational studies

were undertaken to help define a disorder’s characteristics. For example, in 1820 (phrenology’s heyday),

artist Théodore

Géricault

(as a commission for psychiatrist Étienne-Jean Georget) painted a series of ten

portraits of mental patients, each with a different disease.

Géricault and Georget hoped to capture and

define the physical manifestation of each disease. For example, in Portrait of a Kleptomaniac, Géricault depicts a man with a

disheveled appearance, blank eyes, and a frown.

This series of characteristics evident in the painting would then be

used as a metric to determine if other patients had kleptomania.

Théodore Géricault, 1822, Portrait of a Kleptomaniac (image: Wikipedia)

It seems that in this time period, someone’s

appearance is no longer a consequence

of what has gone wrong with someone’s spirit.

A person’s physical appearance is instead indicative of what goes on in the mind, because both are now

understood as having a corporeal origin.

While such understanding led to discrimination in some cases, overall, phrenology

and objective portraiture resulted in kinder treatment to mental patients, because

mental problems were seen as disease-like and out of the patient’s control,

rather than a result of the patient’s sin.

Phrenology also proved revolutionary in society’s relocation of mental

faculties from the spirit into the brain – a belief modern society seems to

hold true, but Victorian society hesitated to accept.

I must end with one thought. I think we should be careful in our pursuit

of answers to the questions of the mind.

Do we really want to know the answers to these questions? It seems like the answers hold the potential

to take all the poetry and magic out of human existence.

Thursday, July 12, 2012

So Anesthesia Was For Adam, But Was It For Eve?

John Snow type Chloroform Inhaler, designed 1858. (Image: geeknews.net).

Today in class we discussed the objections during the 19th century to the use of anesthesia during childbirth for women. As stated in Genesis 3: 16: “in sorrow shalt thou bring forth children…” As far as my knowledge goes, it has always been an issue whether or not a woman should feel pain during childbirth, especially because labor pain has been interpreted time and time again as a punishment for Eve’s transgression in Eden. Of course, my initial, visceral reaction to this statement has always been one of anger and resentment. But my view cannot be applied to the Victorian Era, especially because my modern-day reaction is definitely not indicative of how people felt in the past… in the days before anesthesia.

Hundreds of years ago, before anesthesia, people had to find a way to accept and rationalize pain as acceptable for everyday life. It was seen as a burden that must be borne, or the righteous punishment for all human sin. As an example, a good Christian death involved being totally alert and able to communicate with God, and childbirth was seen in a similar way: as an experience where the woman should be alert and able to receive and call upon God for help. Because of these beliefs, many objected to new Victorian pain relievers such as chloroform because the drug sent the user into a stupor – a state certainly not conducive to communication with God.

Chloroform (Image: web).

Proponents of anesthesia during the Victorian Era often quoted another bible verse in their favor: “So the LORD God caused the man to fall into a deep sleep; and while he was sleeping, he took one of the man's ribs and closed up the place with flesh” (Genesis 2:21). The deep sleep could be represented by chloroform, and God would thereby become the first anesthesiologist. But – did remembering that God used a form of anesthesia on Adam really solve the problem? The bible verse still seems gendered, and I’m sure many still interpreted that way. The bible verses are not mutually exclusive either. It could have been perfectly acceptable for someone to say that God found anesthesia acceptable for Adam and not so for Eve. Did this actually happen? I’m not sure.

Expulsion from Eden, Masaccio, 1425. (Image, http://paradoxplace.com)

I think the painting above might sum up the Victorian inequalities quite nicely, even though it is a Renaissance fresco. The painting depicts Adam and Eve being expulsed from Eden. Adam shamefully hides his emotions but is not required to cover his body. Eve, on the other hand writhes and cries in pain, hiding her genitals from view. In a way, this begins to parallel the situation with anesthesia. Adam (men) would be allowed to hide his emotions and pain under the cloak of stupor, while Eve (women) must still repent for her sin in the Garden of Eden, her face twisted with pain.

Was this inequality the truth, or did people think that the Genesis verse about Adam applied to Eve too? It would certainly be fun to find out.

The Problem with Being a Woman Paleontologist in the Victorian Era

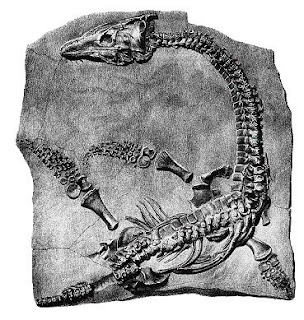

I must comment that I have been very inspired by the essay that we read this week on Miss Mary Anning (1799-1847), “the world’s greatest fossilist.” Mary Anning discovered some of the world’s most beautiful fossil specimens, including the world’s first ichthyosaur as two plesiosaurs. She did not do so easily, however; she was a poor woman from a family of religious dissenters. Her father’s death from consumption had left her family impoverished, and the only way which her family supported itself was to find and sell fossils. This worked for a little while, but when her family had not found fossils in a year, the family was in dire need of money. Luckily, when the Annings resorted to selling their furnishings to pay their rent, another generous fossilist, Lt.-Col. Thomas James Birch, realized the Annings’ need and offered to sell his own collection to raise money for Mary Anning and her family. Lt.-Col. Birch believed that Mary Anning deserved his assistance, because, ultimately, she had found many, if not all, of the most beautiful fossil specimens from Lyme Regis. To Miss Anning’s delight, his philanthropic sale raised 400 pounds for her family -- a sizeable sum of money for people of this time.

Drawing of Ms. Mary Anning's Plesiosaur, 1821.

But, of course Miss Anning’s

problems did not cease. Apparently, some

residents believed that the Lt.-Col.’s fossil sale seemed a little too generous

and, thus, began to spread malicious rumors.

A man who lived nearby commented, “Mrs. Anning is the dealer at Lyme. Col.

Birch is generally at Charmouth (they say Miss Anning attends him).” I gathered from this that many people must

have assumed that a woman such as Miss Anning (especially since she studied

geology, gathered fossils, and interacted with so many men) must have been a

harlot.

When I first read about Ms. Anning,

I did not realize that she carried such stigma.

I was surprised to find out by way of a painting of her:

Painting by William Gray (1842).

As you can see, Mary Anning points

to her dog. Throughout history, dogs in

paintings have often represented a woman’s unfaltering loyalty and good character. The painting below, Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1535), is a portrait of

the courtesan of the Duke of Urbino. The

Duke was quite fond of the courtesan depicted; therefore, he wanted the

painting to depict the courtesan –promiscuous

in reality – as entirely loyal to him, almost as if she were his own wife

(note the marriage chest in the background and the dog to the right of the Venus’s

feet). Like in Titian’s painting,

William Gray included the dog in Miss Anning’s portrait to emphasize that Miss

Anning was truly a woman of discipline and comport.

Venus of Urbino, Titian, 1538.

That the artist felt the need to depict

Mary pointing to her dog is extremely revealing of the degree to which Miss

Mary Anning faced public scrutiny for her unconventional job in a man’s domain

(geology and fossil hunting). I had been

startled when I saw the dog – I knew exactly what its presence was trying to

ameliorate. The dog had been such a pervasive

presence in artwork that its presence had even been satirized by 19th century

artist Manet, who painted a prostitute named Olympia, depicted

below:

Olympia, Manet, 1863. Note the black cat to the right of the painting, and the black servant woman bringing Olympia flowers from an over-enthusiastic 'customer.'

Women have always struggled to free themselves from sexual stereotypes and assumptions. Even to this day, people might assume that women use their sexuality to gain favors or ascend in social status. In the case of Mary Anning, it is a shame that such

malicious assumptions and gossip tainted Miss Anning’s reputation to the point where William Grey's canine intervention was needed. Historically, Miss Anning has hardly been recognized for her achievements. I wonder if malicious gossip contributed to the confusion, and if so, it surely would be tragic. I hope someday that women will be able to escape poisonous, misogynist assumptions!

Sunday, July 8, 2012

Perceptions in Absence of ‘Truth’

When visiting the Cambridge Folk Museum on Thursday, I learned

that, in absence of our modern knowledge of disease, Victorian commoners held

beliefs that might now be classified as quite superstitious. They buried bones or bottles of salt in the

foundations of their houses, placed shoes or bones in their walls, put bones above

their doorways, and hung baubles in their windows to keep away evil spirits

(these baubles may have been the precursor to Christmas tree ornaments!).

A bone to be buried.

Baubles to keep witches away -- the Christmas ornament's ancestor?

These superstitions reminded me of

what I knew about East Asian architecture. For

example, Japanese temples have curved roofs because their society held a belief

that evil spirits could only move in straight lines. A curved roof would thereby impede the evil

spirits’ movement into a temple or dwelling because the evil spirits could not

move upward along the roof. Chinese and

Japanese peoples also believed that sounds would disturb the movement of evil

spirits and keep them away: dwellings

had been built with floorboards that were purposely squeaky, and children (to

this day, I believe) wear shoes that make noises when they walk. Similar to the beliefs about the reflective

baubles, feng shui also includes a belief that hanging a crystal within the

center of a space will improve the movement of qi ('good' energy) within the

space and ward away bad spirits. And

ancient Chinese households would place peach tree branches above doorways to

bring good luck and health to those who dwell within, as peach branches were a

mythical symbol of immortality and had long standing connections to ethereal

peach gardens.

The archetypal East Asian temple roof (Image: web)

Modern feng shui crystals (Image: web)

The cross-cultural pervasiveness of

this class of superstitions appears to reflect the way in which people understood

disease before the medical advances of the 19thcentury. Because common folk were unable to see what

lies beneath a microscope, illness was associated with ‘bad spirits’ rather

than germs, and people appealed to deities and myth rather than scientists for

their answers. I wonder if this model

could apply to our society today – where are the gaps in our knowledge which we

fill with superstition and myth? Are we

able to discern these or are we unconscious of how we take them for

granted? I would assume that these gaps

are likely to include places where we, like ancient peoples, could not completely

see. In our day, this might include the

subatomic and quantum realms.

The Dollar, the Pound Sterling, and the Euro: Technologies that Influence our Perceptions

Upon returning from Italy last January, I was surprised at

how much I missed the euro after beginning to use dollars again. At that point, I wasn’t sure why I had grown

attached to the euro. But now,

especially since I am using a currency quite similar to the euro again – the pound

sterling – I realize that, in my case, forms of currency have changed my

perception of monetary transactions.

Our paper and metal friends, having a party. (Image: rgbnetworks.com)

Aesthetically,

the dollar vastly differs from the pound and the euro. While all dollar bills are relatively monochromatic

(shades of dull green on beige), each differently valued bill of pounds or euros has

its own hue. Different from the dollar,

the pound’s and euro’s bill sizes also change with value – a 5 pound/euro bill

is much smaller than a 10, 20, or 50 pound/euro bill. The size of the bills with the pound and euro

increase incrementally, and this leads the currency-holder to quickly be able

to determine the bill needed. Also, the

brightly colored bills seem to invite the user to spend them, much like

colorful birds hoping to find their mates.

I realize that I enjoyed these qualities; I liked being able to find the bills quickly, and I also delighted in the colors of the bills and I was excited to have them in my wallet and use them. In light of these differences and my own personal anecdotes, I wonder about what sort of effect the aesthetic qualities of a currency has on the frequency of transactions within a country. I haven’t been in England long enough to evaluate the effects of the pound on my spending habits, but I’ve certainly felt the sting of trying to wrap my head around the true value of my purchases (where a 5 pound meal is worth a rough $8).

The euro, in its colorful beauty. Note the architecture featured on it! (Image: pandaamerica.com)

The pound is a bit more subdued than the euro, but it is still incrementally sized. (Image: web)

I realize that I enjoyed these qualities; I liked being able to find the bills quickly, and I also delighted in the colors of the bills and I was excited to have them in my wallet and use them. In light of these differences and my own personal anecdotes, I wonder about what sort of effect the aesthetic qualities of a currency has on the frequency of transactions within a country. I haven’t been in England long enough to evaluate the effects of the pound on my spending habits, but I’ve certainly felt the sting of trying to wrap my head around the true value of my purchases (where a 5 pound meal is worth a rough $8).

Furthermore, I’ve noticed that both

my classmates and I have had problems acclimating to a frequent use of one and

two pound coins when buying things.

Several people have large stockpiles of coins that they do not carry

with them – surely this adds up to a large amount of money that has become

stale! As Americans, we struggle a bit

because we’re in the habit of stuffing coins away in discreet places. So, in England, it’s disturbing to realize

that you’ve got 14 pounds in coins that you had just forgotten. Ultimately, I wonder if these differences have effects that might be noticed on a societal or economic scale. Also, does the aesthetic experience of the currency have effects on spending readiness?

Do you really want to part with your friendly Darwin? Or the beautiful hummingbird? (Image: conservationreport.org)

In the process of writing this blog,

I also came up with another few questions that might be more related to the

course – does a currency help to solidify a country’s perception of its own master

narrative? For those who don’t know what

I’m referring to, a master narrative is a description of an object

or phenomenon’s history that hopes to explain its entire essence by mentioning and linking several pivotal events or information. As we realized in class, the process

of developing a master narrative can be flawed because the process of writing a narrative inevitably privileges certain historical events, concepts, or figures over others. For example, in the case of the U.S.A.'s master narrative, people refer to the founding fathers and the Bill of Rights, but neglect to include other information such as the presence of Native Americans upon the puritans’

arrival, and the many horrible transgressions against them, such as the Trail

of Tears. How would America be different

if Native Americans were part of the prevailing master narrative?

I might argue that currency plays a

part in defining a country’s master narrative.

In the U.S., the figures who confront us every day on our currency are

figures such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Abraham Lincoln, and others. In contrast, I was surprised to find Charles

Darwin on the English 10 pound bill. Then, when researching past figures on pound sterling bills, I noticed that Isaac Newton and Michael Faraday had been on previous

bills. All of these figures are definitely part of England's master narrative, Cambridge's master narrative, or the master narrative of scientific discovery. Bearing the symbolic quality of these figures in mind, I speculate that the legacy of the figures on a country’s currency have noticeable effects on the country’s overall image

and also its master narrative; although, I must admit that I don’t really know the exact nature of these effects or where to look for them.

Elizabeth Fry also appears on the pound... one must admit that it's pretty freaky to find two important figures you're talking about in class perpetually following you around! (Image: catalystmin.org)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)