I must comment that I have been very inspired by the essay that we read this week on Miss Mary Anning (1799-1847), “the world’s greatest fossilist.” Mary Anning discovered some of the world’s most beautiful fossil specimens, including the world’s first ichthyosaur as two plesiosaurs. She did not do so easily, however; she was a poor woman from a family of religious dissenters. Her father’s death from consumption had left her family impoverished, and the only way which her family supported itself was to find and sell fossils. This worked for a little while, but when her family had not found fossils in a year, the family was in dire need of money. Luckily, when the Annings resorted to selling their furnishings to pay their rent, another generous fossilist, Lt.-Col. Thomas James Birch, realized the Annings’ need and offered to sell his own collection to raise money for Mary Anning and her family. Lt.-Col. Birch believed that Mary Anning deserved his assistance, because, ultimately, she had found many, if not all, of the most beautiful fossil specimens from Lyme Regis. To Miss Anning’s delight, his philanthropic sale raised 400 pounds for her family -- a sizeable sum of money for people of this time.

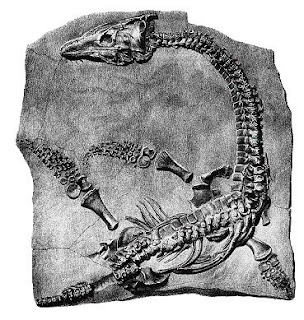

Drawing of Ms. Mary Anning's Plesiosaur, 1821.

But, of course Miss Anning’s

problems did not cease. Apparently, some

residents believed that the Lt.-Col.’s fossil sale seemed a little too generous

and, thus, began to spread malicious rumors.

A man who lived nearby commented, “Mrs. Anning is the dealer at Lyme. Col.

Birch is generally at Charmouth (they say Miss Anning attends him).” I gathered from this that many people must

have assumed that a woman such as Miss Anning (especially since she studied

geology, gathered fossils, and interacted with so many men) must have been a

harlot.

When I first read about Ms. Anning,

I did not realize that she carried such stigma.

I was surprised to find out by way of a painting of her:

Painting by William Gray (1842).

As you can see, Mary Anning points

to her dog. Throughout history, dogs in

paintings have often represented a woman’s unfaltering loyalty and good character. The painting below, Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1535), is a portrait of

the courtesan of the Duke of Urbino. The

Duke was quite fond of the courtesan depicted; therefore, he wanted the

painting to depict the courtesan –promiscuous

in reality – as entirely loyal to him, almost as if she were his own wife

(note the marriage chest in the background and the dog to the right of the Venus’s

feet). Like in Titian’s painting,

William Gray included the dog in Miss Anning’s portrait to emphasize that Miss

Anning was truly a woman of discipline and comport.

Venus of Urbino, Titian, 1538.

That the artist felt the need to depict

Mary pointing to her dog is extremely revealing of the degree to which Miss

Mary Anning faced public scrutiny for her unconventional job in a man’s domain

(geology and fossil hunting). I had been

startled when I saw the dog – I knew exactly what its presence was trying to

ameliorate. The dog had been such a pervasive

presence in artwork that its presence had even been satirized by 19th century

artist Manet, who painted a prostitute named Olympia, depicted

below:

Olympia, Manet, 1863. Note the black cat to the right of the painting, and the black servant woman bringing Olympia flowers from an over-enthusiastic 'customer.'

Women have always struggled to free themselves from sexual stereotypes and assumptions. Even to this day, people might assume that women use their sexuality to gain favors or ascend in social status. In the case of Mary Anning, it is a shame that such

malicious assumptions and gossip tainted Miss Anning’s reputation to the point where William Grey's canine intervention was needed. Historically, Miss Anning has hardly been recognized for her achievements. I wonder if malicious gossip contributed to the confusion, and if so, it surely would be tragic. I hope someday that women will be able to escape poisonous, misogynist assumptions!

No comments:

Post a Comment